The Irony of Fabergé Eggs: Mourning Jewelry for Alexander III

Memento mori miniature egg and shield pendants with monogram of Alexander III

Gunmetal and gold

By Fabergé, St. Petersburg, workmaster M. Perchin

Egg: 2 x 1.2 cm; shield:Â 3.2 x 1.8 cm

These two miniature gunmetal and gold pendants memorialize Tsar Alexander III (1845 -1894). Appropriately somber in tone, the egg lacks ornament but for Alexander’s monogram and crown. The similarly adorned matching shield pendant bears his monogram and crown on the obverse with his date and time of death on the reverse: 2:15 am, October 20, 1894.

Gunmetal’s dark hue aptly signifies mourning and its sturdy nature make it a fitting tribute to the great autocrat.

An alloy of copper, tin, and zinc, gunmetal is a resilient material, valued for its ability to withstand heavy loads and resistance to corrosion. These qualities match Alexander III’s character and strength of body. The Victorian journalist and biographer Charles Lowe described Alexander III as the man with the iron mask, referring to his reserved public persona, but the Tsar was a man of iron in many ways.

The assassination of his father, the great reformer Alexander II, significantly impacted the course of his reign. Hardened by the consequences of his father’s leniency, Alexander III ruled with an iron fist and staunchly defended autocracy. Described as herculean and the Russian Samson, the six foot four burly Tsar was an imposing, strong man. He could bend, and then re-straighten, iron fire pokers, crush silver rubles in his fingers, and tear double packs of cards in half, and he often performed these marvels for the amusement of his children and assembled guests.

His great strength famously came of use in 1888 when the Imperial train derailed and Alexander held up the wrecked carriage’s roof on his shoulders while his family escaped. No one at the time could have guessed that this strong body belied growing weakness. In this moment of heroism, the Tsar bruised a kidney, considered to be the root of the nephritis that ultimately killed him. In the words of biographer Charles Lowe, nobody had any idea that a malignant disease was gnawing at the apparently robust man in the prime of his life.

Years later after the accident, in 1894, Alexander’s health began to rapidly deteriorate. Diagnosed with terminal kidney disease that year, a heavy cold exacerbated an already weakened condition. His worsening health in September prompted a move to the country palace of Livadia in the Crimea, hoping he would improve in a warmer climate. Unfortunately, his condition worsened.

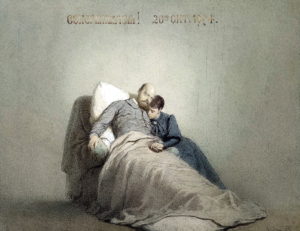

Empress Maria Feodorovna with the body of Alexander III (from the album Death of Alexander III in Livonia), Watercolor and pencil on paper, 1895, Mihaly Zichy (1827-1906), Wikimedia Commons

Biographer Charles Lowe wrote of Alexander’s wife,

The Empress [Maria Feodorovna (1847-1928)] was almost beside herself with grief, but up to the last minute she nursed her husband with the most devoted care. She took no rest. Day and night she was beside her consort, holding his hand in hers, keeping back her tears with all her strength, and softly whispering words of hope. I have even before my death got to know an angel, the Tsar said, pressing her hand to his lips.

Maria wrote to her mother,

He was fully conscious until the last moment, speaking and looking at us until he quite calmly fell asleep into eternal life without any great struggle and in my arm!

Oh, but how heart-rending it was! Incredible that one can survive such sorrow and despair, and now the eternal longing and emptiness everywhere where I am! How shall I bear it? And the poor children, how desolated they are, too, and poor sweet Nicky especially, who has to start that burdensome life while still so young. They are so charming with me, all of them, so full of love and warm feelings. Alicky also shows me so much fond sympathy, which really binds her still closer to my heart.

This egg pendant belonged to Alexander and Maria’s daughter, Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna (1875-1960). It was recorded in her inventory of Easter eggs, a collection of descriptions and watercolor illustrations of Easter eggs and other smaller pieces of jewelry that she acquired between 1880 and 1905, totaling 499 pieces. This inventory page is illustrated in the 2002 exhibition catalogue Treasures of Russia Imperial Gifts.

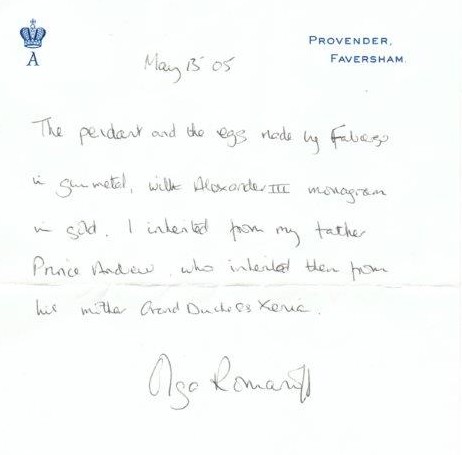

Of the mourning pendant, Xenia recorded that she received it from Aunt Michen (Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Elder (1854-1920)). Xenia passed the pendant onto her son, Prince Andrei Alexandrovich, who passed it on to his daughter, Princess Olga Andreevna. Accompanying the pendants is a letter from Princess Olga stating their provenance:

While eggs are traditionally emblematic of life, this egg pendant embodies grief, a sentiment more connected to the famous Fabergé Easter eggs than their opulence implies. Tsar Alexander III began the Romanov tradition of commissioning the eggs. Wishing to comfort Maria, traumatized by Alexander II’s death, he had the idea to give her an Easter egg in the style of one she liked from her childhood home in Denmark. So pleased with Fabergé’s creation, Alexander and Maria granted him an Imperial Warrant to make an Easter egg every year, in addition to other commissions.

Initially a remedy for grief, Fabergé eggs became annual tokens of affection emblematic of life. To this day, they are forever associated with Romanov splendor. While simple in ornament, these gunmetal and gold egg and shield pendants are no less precious. Together, they are a testament to the loss of a tsar and his lost world.

For all our ALVR Blog posts, please click here.

745 Fifth Avenue, 4th Floor, NYC 10151

1.212.752.1727

Terms of Sale | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

© A La Vieille Russie | Site by 22.