Hidden Histories: The Man Behind the Curtain – Theater Designer Léon Bakst

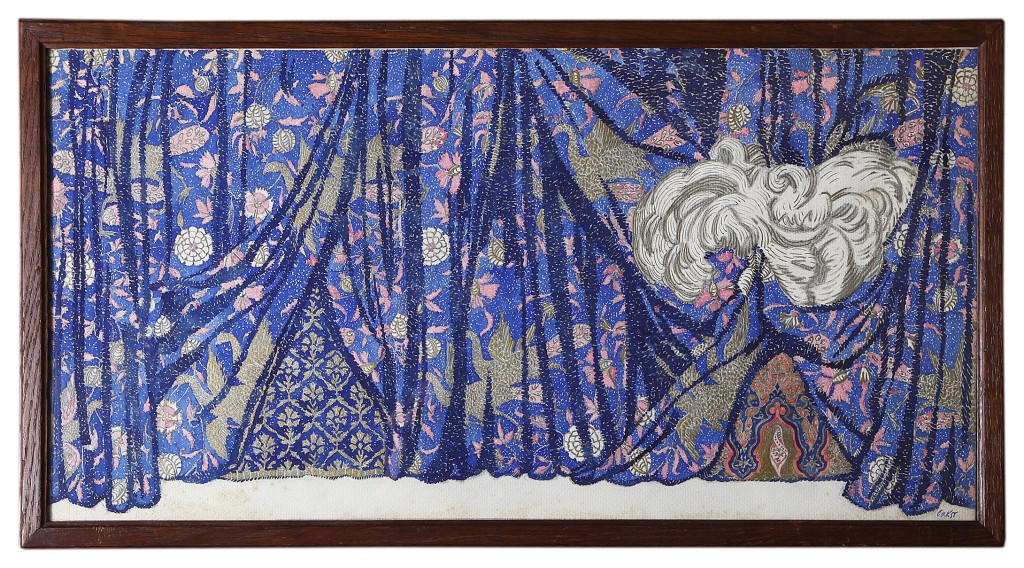

Design for a theatre curtain for the ballet Istar circa. 1924

Watercolor on paper heightened with gold

13-1/4 x 26-1/4 in.

Signed, lower right: Bakst

It seems fitting to conclude this Hidden Histories series with a curtain call. Pictured above is a curtain design for the Ballets Russes by Léon Bakst (1866-1924).

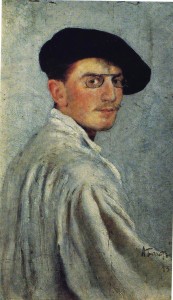

The world-renowned artist and theater designer was born Lev Samoilovich Rozenberg in Grodno, Russia (now Hrodna, Belarus) into a lower middle-class Jewish family. His talent emerged early and at age twelve he won a prize in an art contest, which alarmed his parents. Not wishing to fan the artistic flame, they contacted the famous Russian sculptor Mark Antokolsky, hoping he would discourage Bakst’s artistic pursuits. He did nothing of the sort. Instead, convinced of Bakst’s potential, he praised the young artist.

Perhaps Antokolsky saw himself in the young boy, for, in many ways, the two artists had parallel lives. As emerging Jewish artists, they faced similar hurdles on their paths to artistic greatness. Both were part of a Jewish Renaissance in Russia, when Jews began increasingly embracing secular culture and assimilating into modern life. It has been said that Jewish artists in Russia had two options to either hide or embrace their heritage. As discussed in a previous blog post, Antokolsky managed to straddle both worlds. Bakst, however, as some would argue, appears indifferent to his Jewish roots.

Russian art scholar John Milner said of Bakst’s Jewish identity:

“His Jewishness gave him a skepticism. He didn’t use any Byzantium or Christian themes and nor was he interested in icon painting, which had recently been rediscovered in Russia, because it was Christian oriented. He had a sense of separateness as he did not totally identify with Russian culture.”

Christian art and Bakst’s sense of separateness collided during his enrollment at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. In 1886, his third year of study, he submitted a Pieta for a competition and scandalously contemporized the subjects by depicting Mary and the disciples as impoverished Jews. He was consequently dismissed from the Academy.

Later, at the time of his exhibition in 1889, he changed his name to a variation of Baxter, his maternal grandmother’s name. It has been suggested that Bakst changed his name to sound less Jewish, making it easier to assimilate and rise socially.

Bakst clearly had a conflicted Jewish identity. Upon marrying a Lutheran woman in 1903, he converted. After his divorce in 1910 he returned to Judaism. This renewal of faith later prompted the addition of a Star of David into his personal letterhead, a change he made in the 1920s.

Regardless of his feelings towards his heritage, Bakst successfully made a name for himself through his art. Famed and lauded for his designs for the internationally renowned Ballets Russes, Bakst revolutionized theater design, elevating it to its own art form. Traditionally, theater design color palettes consisted of pale, pastel hues, but Bakst was not one for tradition.

Bakst received great praise for his use of color in costume design by selecting dizzying hues matching the movement of the dancers. This sense of movement is clearly prevalent throughout his theatrical portfolio, exemplified in this curtain design for the 1924 ballet Istar. Theatrical curtains are the audience’s first introduction to a production, and this example must have created quite a bit of excitement and anticipation for the performance.

The shades of green, blue, and pink may seem like a strange combination, yet together they form a vibrant backdrop. The curtain design captures the vibrancy and movement of the stage, with swirls of color and folds of fabric ready to billow and sway out of the frame. The design is imbued with an Orientalist flavor. European artists took inspiration from the East for centuries, a trend that reached a new height in the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. For a Russian artist like Bakst, native to a country which was long conflicted regarding its identity placed between the East and West, Orientalism must have been particularly appealing. Bakst described Orientalism as the Persian and Russian manner mingled. The delicate, naturalistic drawings of pomegranates, flowers and white peacocks heightened with gold are drawn in a simplified manner commonly associated with woodblock printing. These motifs are contrasted against a rich cobalt blue ground. The artist’s signature device of rhythmic movement is evidenced in the parting of the curtains on either side to reveal two different exotic patterns at the base, and in the veils, also heightened with gold, billowing from behind the curtain. The majestic birds may have been inspired by the white peacocks which roamed the garden of the Marchesa Casati, known for favoring a parasol of peacock feathers, whom Bakst met on an early visit to Venice with Diaghilev and Nijinsky.

Bakst treated his set and costume drawings like works of art to be placed on a wall. Here at A La Vieille Russie we present such an artwork housed in the plain, wooden frame original to the workshop. The backing board is stamped with C. [?]asamatt/Depositeur Excluse des oeuvres de Leon BAKST/112 Bd Malesherbes, which may have been stamped when the contents of the artist’s studio were sold. The Metropolitan Museum of Art also has a black and white preparatory drawing for the Istar theater curtain in their permanent collection.

Bakst collaborated with the famous Russian ballerina and patron, Ida Rubinstein, to bring Istar to the Paris Opera, where it had its premier on July 10, 1924. It was among his greatest works and his last to reach the stage. By the time that final curtain fell, Bakst accomplished international renown as an innovative theater designer and artist of great talent.

745 Fifth Avenue, 4th Floor, NYC 10151

1.212.752.1727

Terms of Sale | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

© A La Vieille Russie | Site by 22.