Hidden Histories: Mark Antokolsky’s Portal to Prominence

In mid-nineteenth-century Russia in the town of Vilna, there lived a boy named Mordekhai, but everyone called him Motke. He loved working with his hands, filling makeshift sketchbooks and any available surface with scenes and figures, including walls, tables, and chairs. Even his family’s tavern door was not free of his hand, where he drew a fully armed soldier to frighten away drunkards.

Motke was called leimene hand (clay hands) or leimener geilom (clay statue) for his clumsiness when helping with the family business. Little did anyone know how much these pejorative nicknames prophesized, as those clay hands would one day breathe life not only in clay, but also wood, marble, and bronze. Art history knows him not as Motke or Mordekhai, but Mark Antokolsky (1843-1902), the most famous Russian sculptor of the nineteenth century.

Antokolsky was one of a very few successful Jewish artists in Russia from the nineteenth century. In Russia it was more difficult for Jews to achieve artistic success than in other countries. Artistic pursuits were also not welcomed within the Jewish community. Intellectual training was traditionally revered, unlike art, and all handwork trades, which were looked down upon.

Art was considered frivolous, and figure drawing in particular was taboo. Antokolsky’s parents tried to discourage his artistic inclination, which they regarded as sinful, and his father often beat him for making “idols.†Eventually they relented, and his father arranged for him to apprentice with various artisans. The young sculptor was unhappy with all of them, until he became the pupil of the wood carver Stassel’krout, remaining his apprentice for three years.

His work so impressed the wife of Vilna’s governor-general that she helped him travel to St. Petersburg to receive a stipend from Baron Horace Ginzberg to attend the Imperial Academy of Arts. In 1862 he was the first Jewish student to be accepted at the Imperial Academy of Arts, but only as a volnoslushatel, meaning someone who can attend class but not be put on the official student list.

A combination of such luck and talent laid the foundation for Antokolsky’s success. Starting in the 1860s, a relaxation of restrictive laws, among other factors, made it easier for Jews to acquire artistic training in Moscow and St. Petersburg. At last, artistic portrayals of Russian-Jewish life would no longer be confined to the ethnographic domain, as Jews appropriated their own image.

Antokolsky had one foot in the Russian and European art world and another in the Pale of Settlement, which was a world in and of itself. Though he deviated from tradition in pursuit of art, he would not sacrifice his strong Jewish identity for success. He remained observant by not working on the Sabbath and enthusiastically attended High Holiday services. His Jewish heritage inspired much of his work. In 1864 he received a silver medal for his wood carving Jewish Tailor. This honor was a significant turning point in the representation of Jews in art, as this was the first time in Russian sculpture that an image of a Jew was presented in a dignified manner and not conforming to stereotypes. The prominent art critic Vladimir Stasov praised the work, saying it represented “a launching of the new and true sculpture,†also remarking, “Before Antokolsky, not a single sculptor in the whole of Europe had endeavored to portray scenes of Jewish national life and to become an explorer of these innovative landscapes.â€

One Jewish subject depicted by Antokolsky is the seventeenth century Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677). This portrait, on view here at A La Vieille Russie, was part of a project called the Friends of Mankind, a group of historical and biblical figures Antokolsky admired for their devotion to truth and kindness. Ever devoted to historical accuracy, Antokolsky meticulously researched his subjects and Spinoza was no exception. He pieced together every little biographical detail he could find and was frustrated with the discrepancies encountered in many portraits.  He also went on a trip to Amsterdam to “peep in the environment where Spinoza came from and to breathe in the air there.â€

Antokolsky felt a strong inner bond between Spinoza and himself, as Spinoza’s dual identity paralleled his own: they both challenged tradition, becoming outsiders within and outside of their communities. A descendent of marranos (Jews who converted during the Spanish Inquisition but practiced Judaism secretly or later returned to it), Spinoza was raised in a deeply religious household and educated to become a rabbi. However, he became drawn to secular subjects, particularly philosophy, and began to question aspects of his faith. Accused of betraying Judaism and becoming an atheist, he was excommunicated in 1656 at 24 years old, and later exiled from Amsterdam. Although he never abandoned Judaism and changed religions, his unconventional views were threatening to a Jewish community still recovering from the Spanish Inquisition and concerned with reviving and maintaining traditions.

Antokolsky’s portraits of important figures in Russian history are also highly regarded, two of which are for sale here at A La Vieille Russie. One such portrait is a ceramic bust of Ivan the Terrible. Ivan was produced in a variety of media, including marble, plaster, and silver. Majolica was a rare medium for Antokolsky. Originally executed in bronze in 1871, the portrait won Antokolsky many honors, and he became famous overnight. To become so renowned in one’s own lifetime is a significant accomplishment for any artist, and accompanying this instant fame was a gold medal and the title of  Academician. The portrait impressed Tsar Alexander II so much that he commissioned a copy for the Hermitage, now in the Russian State Museum. As with all his works, Antokolsky meticulously researched Ivan’s life and character, also spending four months in the Kremlin Armory studying designs for the throne and costume.

Antokolsky’s portraits of important figures in Russian history are also highly regarded, two of which are for sale here at A La Vieille Russie. One such portrait is a ceramic bust of Ivan the Terrible. Ivan was produced in a variety of media, including marble, plaster, and silver. Majolica was a rare medium for Antokolsky. Originally executed in bronze in 1871, the portrait won Antokolsky many honors, and he became famous overnight. To become so renowned in one’s own lifetime is a significant accomplishment for any artist, and accompanying this instant fame was a gold medal and the title of  Academician. The portrait impressed Tsar Alexander II so much that he commissioned a copy for the Hermitage, now in the Russian State Museum. As with all his works, Antokolsky meticulously researched Ivan’s life and character, also spending four months in the Kremlin Armory studying designs for the throne and costume.

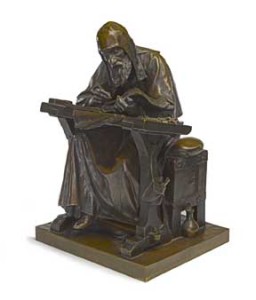

Another notable historical portrait in our collection is a bronze of Nestor the Chronicler, the eleventh century Kievan monk credited as the author of Primary Chronicle, or Tale of Bygone Years, the only written record of Russia’s early history. Antokolsky thoroughly read the Chronicle as he worked on the portrait, and the plain wooden table, clothing, and  other features reflect his loyalty to historical accuracy. The first version of Nestor was made in bronze in 1890 and was over five feet tall. It was originally in the Hermitage and moved to the Russian Museum in 1897.

other features reflect his loyalty to historical accuracy. The first version of Nestor was made in bronze in 1890 and was over five feet tall. It was originally in the Hermitage and moved to the Russian Museum in 1897.

Due to a combination of health problems and anti-Semitic aggression, Antokolsky moved abroad, first to Rome in 1871 and then Paris in 1877, but his heart remained in Russia and he returned periodically. He continued to receive honors, including a gold medal at the 1878 Exposition Universelle, and again in 1900. In 1893 he was named a full member of the Imperial Academy of Arts. He died at the age of sixty-one in 1902, at last returning to the land of his birth, and is buried in St. Petersburg. The young clay hands who once left his mark on his family home, grew up to leave his mark on the world.

For all our ALVR Blog posts, please click here.

745 Fifth Avenue, 4th Floor, NYC 10151

1.212.752.1727

Terms of Sale | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

© A La Vieille Russie | Site by 22.