Hidden Histories:

Roubaud’s Ethnographic View of Jewish Life in Imperial Russia

Franz Roubaud (Odessa 1856-1928 Munich) Village Merchants: Street of Jarmolinzi in Podolien Oil on canvas: 33.5 x 59 inches (85 x 150 cm) Signed and dated lower left: F. Roubaud 1897

This painting, Village Merchants: Street of Jarmolinzi in Podolien, by Franz Roubaud, depicts a village scene in the Podolia region of Ukraine, which, along with other lands formerly part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, became part of the Russian Empire in the late eighteenth century.

The scene befits the title, showing townspeople peddling wares and conducting business transactions. Nearly half of Podolia’s Jews were involved in commerce. The village’s muddy street and modest buildings beneath a grey sky imply the hardships of everyday life.

As viewers we are removed from the scene, observing from a distance, a perspective that matches the marginalization of Jews in Russian society. Jews were restricted to the periphery of the Russian Empire, in what was called the Pale of Settlement. It was initially created to impose commercial restrictions on Jews and generally to prevent integration with the rest of Russia’s population.

In sum, Jews were outsiders, seen as the “other,†and this perception factored into their artistic representation. In Roubaud’s rendering of this village, he was an outsider looking in. He was not Jewish, the son of a Frenchman living in Russia. Renowned for painting grand, panoramic battle scenes, like A Tale of the Caucasus:

Franz Roubaud (Russian, 1856-1928) A Tale of the Caucasus signed and dated 'F. Roubaud/1907.' (lower right) oil on canvas 56¼ x 77½ in. (142.8 x 197.2 cm.)

Village Merchants stands apart from Roubaud’s oeuvre. In this brief break from the battlefield, Roubaud participates in a tradition of non-Jewish Russian artists depicting Jews in art. Starting in the nineteenth century, Russian artists became interested in Jewish life, illustrating their subjects under an ethnographic, as well as artistic, lens.

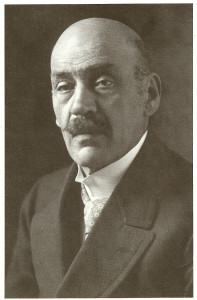

Roubaud, 1916 Reproduced from Hans-Peter Bühler, Jäger, Kosaken und polnische Reiter Josef von Brandt, Alfred von Wierusz-Kowalski, Franz Roubaud und der Münchner Polenkreis. (Georg Olms Verlag, 1993), 142

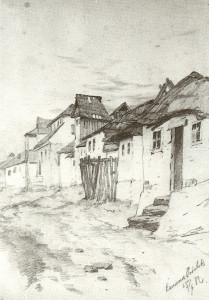

Roubaud began his studies in Odessa, whose significant Jewish population clearly left an impression on the artist. From 1878-1883 he studied at the Royal Bavarian Academy of Arts in Munich, developing his skills particularly under the guidance of the Polish artist Josef von Brandt. Roubaud produced his initial sketch for Jarmolinzi in 1882, which features a close study of the buildings, though devoid of townspeople:

1882 Study, 11.4 x 8.2 in. (29 x 20.8 cm) Reproduced from Hans-Peter Bühler, Jäger, Kosaken und polnische Reiter Josef von Brandt, Alfred von Wierusz-Kowalski, Franz Roubaud und der Münchner Polenkreis. (Georg Olms Verlag, 1993), 134

From the time of this sketch to the painting’s completion in 1897, Russia’s Jews experienced heightened persecution. They were targeted as an easy scapegoat for the 1881 assassination of Alexander II, inciting several pogroms (mob violence) across the Podolia region. This violence, in addition to new economic restrictions enforced by the government, made life increasingly difficult. These factors inspired significant emigration, mostly to North America.

Other aspects of Jewish life have also inspired artistic expression. Contemporaneous with Roubaud’s 1897 painting, the Yiddish author and playwright Sholem Aleichem wrote about life in the Pale of Settlement. In 1894, he penned Tevye and his Daughters and other stories, later inspiring the musical Fiddler on the Roof, which premiered on Broadway in 1964.  The musical’s title and original set design were inspired by Marc Chagall. In the final act, Tevye and his family have been expelled from the fictional village Anatevka and flee to more welcoming shores, singing words familiar to many at the turn of the twentieth century, “soon I’ll be a stranger in a strange new place, searching for an old familiar face.â€

Roubaud’s painting does not reflect such chaos and vulnerability, but a quiet existence. Jewish life in Russia is a multifaceted subject, and Roubaud’s window is but one view.

The next few blog posts will further examine Jewish subjects in Russian art, as well as Russian Jewish artists. While this post explored Jewish subjects in ethnographic art, our next post will highlight Jewish subjects in Russian art by one of their own, the most famous Russian Jewish artist of the nineteenth century, Mark Antokolsky.

745 Fifth Avenue, 4th Floor, NYC 10151

1.212.752.1727

Terms of Sale | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

© A La Vieille Russie | Site by 22.